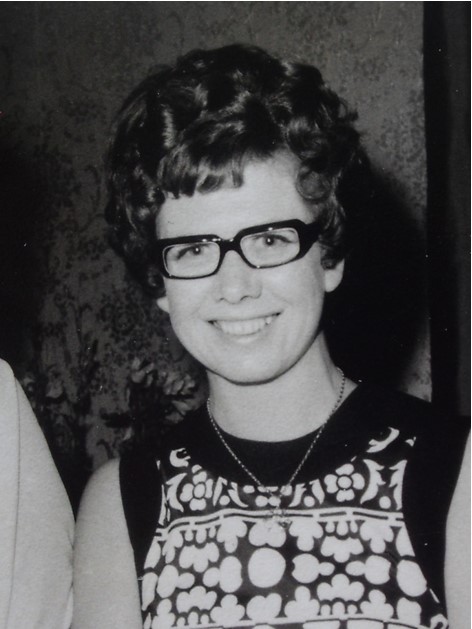

Francie Vagg - Ex Staff Nurse, Staff Sister and Charge Nurse Ward 19

Recollections of Life in Ward 19, 1964 - 1975

I trained at Nelson Public Hospital, and once registered, transferred to Wellington in pursuit of the greener pastures and of course, a man. In my interview with the then Matron, Miss Cook, an immensely forbidding and impressive presence, I asked rather timidly if it would be possible for me to work in an adult surgical ward. So of course, I was sent to the 0-5 year-old children’s medical ward, Ward 19. Apart from a brief stint in the childrens ward in Nelson Hospital while training, I had no experience in paediatrics, and rapidly found it was vastly different from looking after adults. Not as physically demanding, it was otherwise a totally different world, where the patients could not tell you where it was hurting, and screamed when you tried to make it better by sticking needles in them. Sister Helen Whelan was our Ward Sister (as they were known at that time), and she proved to be the making of me.

A wonderful nurse of the old school, where immediate obedience was expected, everything to be done perfectly, and nothing but total commitment demanded. She was a brilliant teacher who expanded and consolidated my training, and taught me so much about children, their needs, and of course their illnesses and treatments.

I stayed in Ward 19 for 3 years advancing to Staff Sister, before leaving for a 15 month trip to Australia. Upon return, for the next five years I worked as a night supervisor, did stints in Emergency and Accident, and the neonatal unit, completed my training as a midwife, and also undertook the advanced nursing studies course. At the end of all this, I returned to Ward 19 as the Charge Nurse in 1972.

Ward 19 was one of the busiest, if not the busiest, of all in Wellington Hospital. Old fashioned by present standards, it was of the Nightingale design which consisted of one main open ward with cots and beds around the perimeter of the room and an open play area in the middle, and an enclosed verandah at one end. The office opened into this area so staff inside always knew what was going on outside. A separated isolation area ran alongside the main ward with windows into the office, and at the opposite end to the verandah there were two half-glazed cubicles for older babies. On the other side of the office and opposite these cubicles was a room used for admitting patients and for carrying out procedures away from the other children. A nursery for newborn and very young babies was situated in a room off the corridor leading to the Ward. Bathrooms, toilets, utility rooms and the nurses change room were located at the far end, and there was a special milk room for preparing formulas off the entry corridor and close to the nursery.

I can’t remember how many beds we had officially, but we had between 40 and 60 patients at peak times, usually during winter. As may be imagined it could be bedlam, especially at feeding times, and when we were especially full with young babies the call would go out for nurses from other wards to help with feeding. It was always great when the ward gradually quietened as babies eagerly took their bottles and the toddlers settled down for a rest after their meals. The main problem of course was that when we were so busy, we had little time to give to each child the love and attention they needed, and of course in those days, parents were only with their children during visiting hours. Not very good by today’s rather more enlightened standards.

It’s hard trying to remember individuals out of all the patients we cared for, but there are three who will never leave me. The first one was baby J who at about 10 months was admitted with haemolytic uraemic syndrome. He was desperately ill, and needed to be cared for in an intensive care unit. But we knew that the nurses there, brilliant as they were, did not know how to look after babies, so we insisted that we would look after him. And so we became a one-patient intensive care unit. We separated a section of the verandah for him, and set it up with all the paraphernalia and equipment essential for his care. A special team was rostered round the clock, and I remember doing my usual shift from 7am – 3.30pm, going off for a quick break then returning at about 7pm and working through the night to the next morning. And that was not unusual, many of the nurses did the same. After weeks of intensive care, J recovered to become a bonny bouncing boy, full of energy and happiness. We all loved him, and saw him go home with sadness. I have often wondered how he did in life.

Another wee baby we had was P, who suffered from a twisted bowel at about 2 months. Following surgery he had many complications, with a recurrence, wound infections, etc, resulting in extensive bowel resections. He was a lovely little boy, very patient and uncomplaining during the long months we cared for him before he finally turned the corner and we were able to send him home, fully cured.

One of our longest-staying patients was O, who suffered from terrible asthma from a very young age, about 6 months. He was treated with huge doses of steroids in the efforts to control it, which stunted his growth, but his asthma was never really totally under control. O became a fixture in the Ward, with frequent visits especially during winter, and eventually outgrew us and moved up to Ward 17 where the older children were looked after. Hilary knows more about what happened to O, as she helped to look after him in her specialist nurse role.

Looking after children is not easy, because as I said before, they cannot tell you where it hurts. Also of course, you cannot explain what is going to happen, nor give reassurances that they can understand, because it is all outside their understanding. However of course, once they have experienced their first needle, that is never forgotten, and we learned to be extremely cunning at times! Separating the children from their parents was always hard, and of course nowadays we look back with horror to think that we thought that was the best thing for them.

Some procedures I never got over, the worst being spinal taps, or lumbar punctures. That was one procedure I hated assisting with, especially when it was a child with meningitis, when to curve their backs to separate the vertebrae caused them extreme pain. Meningitis was then and still is a dreadful disease, causing in the most extreme cases death very quickly within hours of symptoms first showing. I also hated giving injections, and had to steel myself each time. Strange isn’t it, you would think it would get easier but it never did.

It wasn’t all doom and gloom. There were lots of times when it was great fun, playing with the recovering children and staff hi jinks. Seeing children starting to relax and smile and laugh as they start to trust you and get better makes for a happy work place, and that is mostly how I remember the ward. However, there were dramatic moments as well. I remember one occasion when I was one night duty in my Staff Nurse days. It was in the middle of summer, and very hot, so we had the verandah windows open to let in fresh cool air. The windows were those marvellous old Victorian types, double hung, which could be opened from both bottom and top, and we had all the bottoms open to avoid drafts over the cots. We suddenly became aware of strange noises coming from the verandah, and upon shining the torch around saw a huge possum scrabbling around on the polished floor. Well, we panicked, the possum panicked and bedlam resulted. The beast shot off into the main ward, and of course we were terrified it would injure one of the children, and we were also desperate not to waken them. However, we opened all the windows in the ward, and after quietening down it eventually found one of them and disappeared outside. The bottom windows were always kept firmly shut after that, and that night report must have made very interesting reading the next day!

There were also some very scary moments. I remember one day I was in the office when the lights flickered and at the same time there was a bang out in the glazed cubicle area. Running around we were asking each other what on earth was that when we noticed a toddler lying on the floor looking dazed, and alongside him was a very peculiar metal object with many prongs on it. Putting one and one together we realised that he had somehow got hold of this thing and thought to turn it on in one of the electric plugs! How he was not killed I do not know. Thankfully the connection was violent enough to throw him away to immediately break the current. We made very sure after that all the plugs were fitted with caps. But that was still not enough when some time later I was again in the office and there was a similar flicker to the lights, but no bang this time. I knew immediately what it was, and chanted Oh no – please let it be alright as I flew around looking for signs of a (hopefully) dazed child. Finally I found a little girl under a bed in the treatment room, the sister of a newly arrived patient who had found her mother’s knitting needle and crawling under the bed took out the plug and inserted it into the socket. Thankfully she was alright as well, but it took another ten years off my life.

In an effort to make life in the ward more normal for the children and parents I introduced a trial of wearing mufti clothes. I remember it was my first attempt at writing a report with a genuine result in mind rather than the academic ones we wrote for study purposes. The trial went well, although the powers that be refused to officially support it, and would not agree to funding, so we had to use our own clothes and do our own laundering. It was voluntary, so some nurses continued to wear uniforms, while others whole-heartedly embraced the more relaxed style. I like to think that we among the first in New Zealand (more relaxed regimes were being introduced into hospitals in Europe as well at that time) to move away from the starched caps, veils, uniforms, cuffs and belts we used to harness ourselves into before each duty. Those veils were a pain – you cannot lift an adult patient up in bed while wearing one! And they took about an hour to iron. I still have some of mine – made of beautiful fine lawn cotton, I used them to strain my home-made ginger beer for years!

All nurses in specialty areas, and even ‘ordinary’ wards, have preferences for certain types of illnesses and patients, and we worked with those preferences in Ward 19. Each trained nurse worked with patients in her preferred area, as far as possible staying with them throughout their stays. But of course, when needs must everyone pitched wherever the work was required. We also had Karitane nurses to help with the neonates and young babies, and they were great with their specialist knowledge and understanding of looking after infants. We also had physiotherapists and social workers who worked exclusively in paediatrics, which was essential given their special needs.

Even with one of the biggest staff in the Hospital, around 30 trained nurses plus trainees, we worked really hard. Long hours without meal breaks, and long shifts without days off. It was not uncommon to work 10 – 12 hours a day for 10 or 12 days without a break, or to do night duty, have a sleep and do an afternoon shift on the same day. I remember once when still a staff nurse after a particularly gruelling period when none of us had had a break for more than fortnight, during our half hour lunch break taken at 2pm after 7am start, a group of us rebelled, and resolved to send a letter of complaint to the matron, signed by all of us. It caused quite a stir because nurses were supposed to be noble and ready to sacrifice all for their duty. Well, we were visited by the Matron and her retinue, but nothing really happened. I think we did get some more help with feeding, but that was about all!

It was during my time in Ward 19 that I developed the confidence in my own knowledge and expertise to go against orders for the sake of the patients. We often had babies admitted with pyloric stenosis, who, after being operated on, were put on a very strict feeding regime. This consisted of painstakingly feeding them tiny amounts of an electrolyte solution through their nasal gastric tubes, for 24 hours after the operation. Well, these babies had been starving before they had their ops, because they were vomiting everything they took down, so they were ravenous. And we added insult to injury by giving them this totally unsatisfying water. Despite our pleas that the regime be speeded up the surgeon refused to listen nor to change his system, so I decided that more potential damage could be caused from constant screaming from hunger, than would be caused by increasing the rate of feeding and adding milk solution more quickly than the regime called for, keeping in mind the need to protect the surgery, but also recognising that babies heal much faster than adults. So surreptiously, and carefully watching how they progressed, we modified the surgeon’s routine, much to the satisfaction of the babies and with a huge improvement in the noise levels in the nursery. The surgeon never knew, and I won’t name him now because he might still be around - I would hate for him to realise that we were deliberately disobeying his orders!

Towards the end of my time as charge nurse an innovative approach to nursing was trialled, that of nurse specialists. There were two in the Hospital, an adult surgical specialist and a paediatric one, Hilary Harper, now Patton. What a difference that made. We had already been working with a team approach for the care of each child, with regular meetings between nurses, social workers, physios etc., but for the first time there was someone at hand to take on patients with special needs, either physical, mental or social, or perhaps all three. The specialist nurse was able to look at the whole patient and their families, including family circumstances, total history, and to work with a team including social workers, physio and occupational therapists, doctors, and community nurses. It was an immense relief to know that there was someone with the time and skills on hand to make sure that these special patients were getting much improved care, and you could see from the results that return visits were much reduced, recovery times were better, and family participation was improved. It was also during this era that we began to encourage parents to stay longer with their children, although overnight stays were not really possible because of the almost total lack of facilities.

Even though it was obvious that patient care was much improved, those holding the purse strings decided that nurse specialists were too expensive and the trial was brought to an end. There was much ranting and railing, gnashing of teeth and dire imprecations against bean counters, all to no avail. When you think of the savings quick interventions and proper care made to the numbers of admissions, length of stay and reduced return admissions, it was vastly more economical to use and actually increase the type of care specialists were able to give, but all the bean counters were interested in was the immediate cost, and two specialists salaries were too much for their beloved budgets, so they had to go. Don’t get me started.......

This was also the age where doctors became more involved as part of the team, rather than the traditional practices of fleeting visits (The Grand Round) to inspect and issue orders. That sounds harsh, but when I started nursing that was the way of it. We had marvellous medical people, Professor Jeff Weston, Brian Corkill for neonates, Richard Bush, Athol Arthur, and all the visiting specialists. There was a continual circulation of wonderful registrars and house surgeons who all needed training up on how to change nappies and properly feed babies. They were not allowed to examine a baby and leave him or her unchanged. Those who did were never any good and never stayed. A simple measure of worth but reliable! The nursing staff were respected and their opinions valued and actively sought as equal members of the team. As they should have been because, especially towards the end of my tenure, specially trained and highly experienced paediatric nurses from Canada, Britain and of course New Zealand were in the Ward team. I believe they would have been one of the most highly trained staff in the Hospital outside the ICU and cardiothoracic units.

I set up a tropical fish tank in the main ward, and among the many fish was a black sucker fish which we called HJ after Jeff Weston. He pretended to be insulted but was secretly rather proud that he was the only one with a fish named after him! That tank helped sooth and calm many a poor lonely child after their parents had left the ward.

That is a very brief summary of my memories of Ward 19. There are many more – funny old foreign tea ladies, kittens under the floor, crying in the linen room, scrubbing nappies, wonderful friends, folding nappies, lots of laughter and tears, carrying dead babies down to the morgue, picnics with the children on the lawn, Jan the Ward Clerk trying to instil order into the day, trying to work out insulin doses with fingers crossed (maths was never a strong point), immense satisfaction seeing a desperately ill child recover and go home, watching children gradually accept and trust us, bedlam when the well children were full of energy, making beds when the air was full of static electricity (very painful), feeding time when the ward was quiet and the children contented. And of course all the staff – too many to talk about individually, but all wonderful, dedicated and very, very special. Even though it was only a small part of my working life, it was the most rewarding and special time, and I was very lucky indeed that my request for an adult surgical ward was ignored!